For millions of people around the world, Amazon is a go-to source to buy everything from toys to toilet paper — a panoply of goods that can be shipped to your door in two days or less. But while this level of convenience has allowed the tech giant to claim more than 40 percent of the e-commerce market share, some argue that it comes at the expense of employees — especially those working in Amazon warehouses, who are held to exacting standards and monitored constantly during shifts that can be long and exhausting.

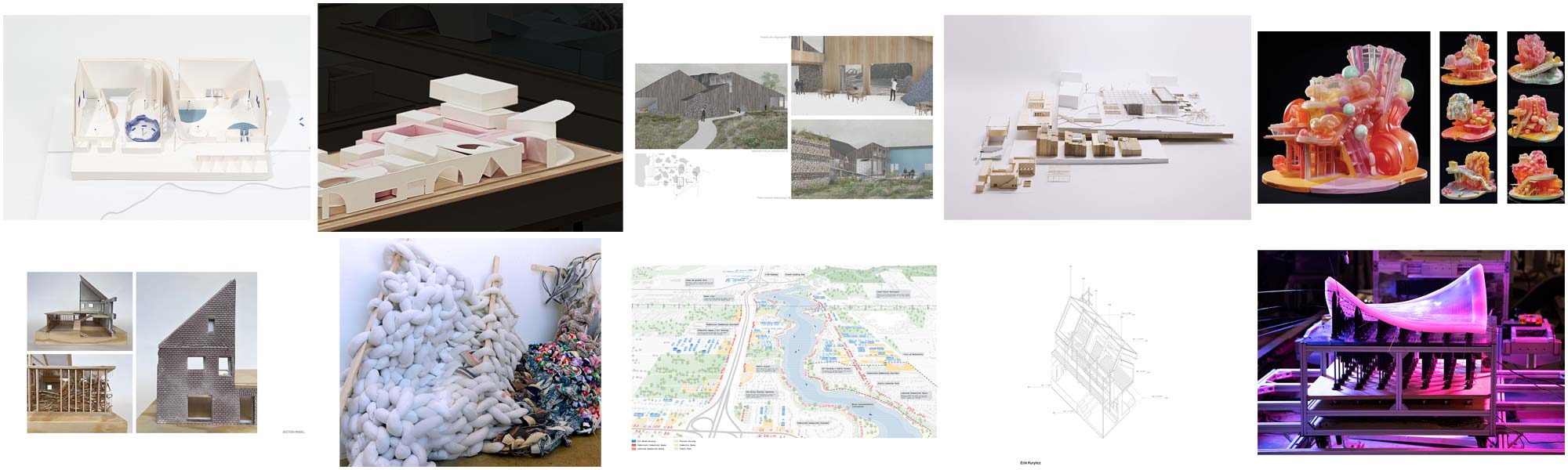

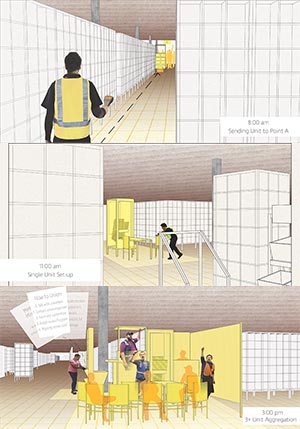

“They just burn through workers — that’s part of their strategy,” says Willow Davis, B.S. ’18, who explored the issue for a Wallenberg Studio project in 2018. “They don’t want to retain people long enough for them to form unions or ask for better pay.”

The Humanitarian Side of Architecture

The plight of Amazon’s workers might not sound like a problem for architects to solve, but the Wallenberg Studio presents a more open-ended brief — that year, for example, the theme was “Agency.” Long concerned about workers’ rights, Davis began to think about how design might give more agency to Amazon employees and allow them the space for rest, relief, and organizing that their workplaces did not currently provide. The result — informed by interviews with actual Amazon employees — was a project Davis called “Cloaked Communications.” It reimagined the 3’x3’x8’ shelves that Amazon’s robots carry along its warehouse floors as mobile break stations where workers could store lunches, folding chairs — and perhaps union pamphlets, allowing workers to build covert solidarity.

The plight of Amazon’s workers might not sound like a problem for architects to solve, but the Wallenberg Studio presents a more open-ended brief — that year, for example, the theme was “Agency.” Long concerned about workers’ rights, Davis began to think about how design might give more agency to Amazon employees and allow them the space for rest, relief, and organizing that their workplaces did not currently provide. The result — informed by interviews with actual Amazon employees — was a project Davis called “Cloaked Communications.” It reimagined the 3’x3’x8’ shelves that Amazon’s robots carry along its warehouse floors as mobile break stations where workers could store lunches, folding chairs — and perhaps union pamphlets, allowing workers to build covert solidarity.

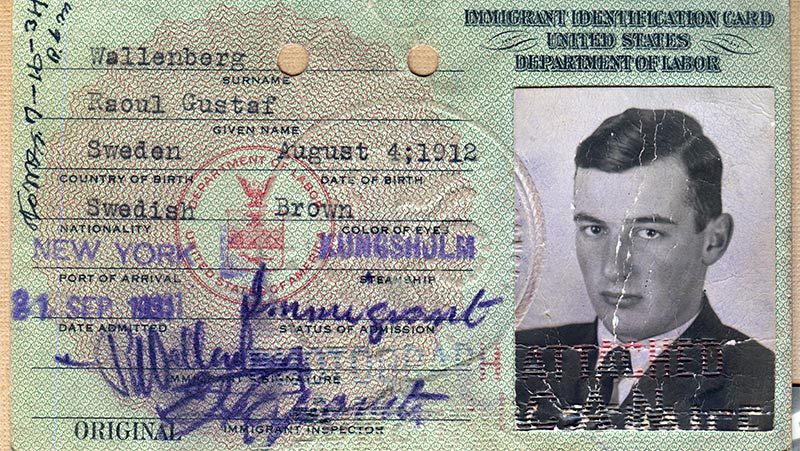

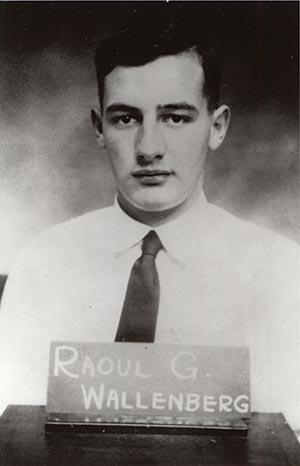

The required, culminating studio for seniors in Taubman College’s Bachelor of Science in Architecture program, the Wallenberg Studio — named for humanitarian Raoul Wallenberg, B.Arch ’35 — asks students to focus on the humanitarian aspects of architectural design. For Davis, it helped crystallize the way she thinks about her profession, not only as a creative discipline, but as a way to serve the humans who live and work within the built environment.

“I feel like the whole culture of Taubman College helped with that, but having the Wallenberg Studio as a capstone really solidifies those values,” says Davis, now an architectural intern in Chicago working on projects for religious and cultural institutions. “You can pick up the more technical things anywhere. It’s harder to pick up the humanitarian side.”

It’s an idea that Professor Sharon Haar, who chaired the architecture program from 2014 to 2019, has heard from many students over the years. “I think that the Wallenberg Studio is really important to them,” she says. “And that’s because it does things that no other studio or class that they take does. It connects them to a legacy of humanity and humanitarianism, and it allows them to see the world, urban space, and the physical environment differently. It helps them figure out what sort of architect — and what sort of person — they want to be.”

Supporting Students, Honoring a Hero

Raoul Wallenberg was the scion of a wealthy family of Swedish bankers and diplomats. His grandfather encouraged him to pursue an American education, and Wallenberg, who was interested in architecture, chose Michigan because it had one of the country’s top programs but wasn’t housed at what he considered an “elitist” institution.

Arriving in Ann Arbor in 1931, the young man known to friends as “Rudy” brought true dedication to his architecture classes, winning the American Institute of Architects medal as the top student in his class. Although his American credentials did not let him practice in his native Sweden, the skills he honed at Michigan would serve him in other ways.

Arriving in Ann Arbor in 1931, the young man known to friends as “Rudy” brought true dedication to his architecture classes, winning the American Institute of Architects medal as the top student in his class. Although his American credentials did not let him practice in his native Sweden, the skills he honed at Michigan would serve him in other ways.

In 1944, less than a decade after graduation, Wallenberg traveled to Budapest under diplomatic cover. He issued forged documents that identified Hungarian Jews and others as citizens of Sweden — a neutral country — who were awaiting repatriation, thus protecting the bearers from deportation to the death camps. Wallenberg also rented buildings in Budapest, declared them part of the Swedish diplomatic delegation, and used them as safe-houses for thousands of Jews. He personally intercepted a train en route to Auschwitz, climbing on its roof and issuing “protective passes” through the windows. In the end, Wallenberg saved as many as 100,000 people from the Holocaust.

“Wallenberg didn’t build buildings in Hungary,” Haar notes. “But he understood physical space and how the city was organized, so he could move people around it very carefully. These things come from his experiences at Michigan and the connections that he made here.”

Soviet forces arrested Wallenberg as a suspected spy in 1945, and to this day his precise fate remains unknown. Still, after World War II he would be recognized as one of the greatest humanitarians of his age, earning honorary citizenship in the United States, Canada, Hungary, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Israel.

In 1985, David Engelbert, B.B.A. ’58, was serving as the executor for the estate of Detroit industrialist Benard L. “Ben” Maas (1896–1984) and administrator of his namesake foundation. While Maas had no connection to U-M, he was “deeply committed to helping young people” and his foundation aimed to benefit education, Engelbert says. Meanwhile, Engelbert, who was a child when World War II ended, had long been awed by Wallenberg’s heroism, so he approached his alma mater’s College of Architecture and Urban Planning with an idea for a way to honor both Wallenberg and Maas.

“I was amazed to learn that [Wallenberg] had been a student here in the 1930s,” Engelbert remembers. “To have saved so many lives, and in the way he did it, was epic…. We are pleased that this is a gift that keeps on giving. Ben would be pleased with the wonderful impact his funds are having with the students involved.”

Initially intended to provide tuition assistance, the Raoul Wallenberg Scholarship Fund now covers travel grants for Wallenberg Studio groups, as well as international travel stipends for students whose Wallenberg Studio projects are deemed the most outstanding in a juried competition each year (Willow Davis won a travel award in 2018, allowing her to visit Japan). Meanwhile, Wallenberg’s legacy infuses the work of the studio.

Self-reflection on the Hardest of Questions

“The studio does more than just address social issues,” says Mireille Roddier, an associate professor of architecture who has taught and coordinated the Wallenberg Studio many times since coming to Taubman College in 2000. “It’s also about asking very hard questions of architecture and learning to be contented with the limits of what architecture can or cannot take on.”

Roddier most recently coordinated the Wallenberg Studio in 2020 with the theme “From the Margins,” a nod to bell hooks’s essay. Just weeks before the pandemic ground travel to a halt, she and Dawn Gilpin, a lecturer in architecture, took their Wallenberg students to the Arizona desert and the experimental utopia Arcosanti. In 2021, the theme was “Resistance.” The theme had a personal resonance for Roddier, whose grandfather was a member of the French Resistance during World War II. He died when she was 19 years old, but her memories of him are vivid — as is her understanding that Raoul Wallenberg’s life and times are not that far removed from our own.

“Architecture operates in the service of money and power and capital,” Roddier says “Are we always complicit? Every time I have coordinated the Wallenberg Studio, I have started from the notion of resistance. What does it mean to resist, and what does it mean to be complicit? The best Wallenberg students just bloom when they’re confronted with these hardest of questions.”

Lecturer Dawn Gilpin won the ARCHITECT Studio Prize in 2016 for her Wallenberg Studio, “The Radical and the Preposterous: Mind the Gap.” That year, the theme was “Refuge,” and Gilpin asked her students to consider the global refugee crisis, broadening their perspective through a reading list that included Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism as well as real-time interviews with people working in refugee camps around the world.

Gilpin, who teaches interdisciplinary seminars, design studios, and pre-architecture representation and drawing courses, enjoys seeing Taubman students progress from mastering these first concrete skills to what she calls the “pseudo-thesis” of their Wallenberg Studio projects. “It’s always amazing to be a part of a student’s final semester, working with them to position their interests and their voice within architecture,” she says.

Learning How to Use Their Power

There’s a lingering stereotype of the architect as a lofty genius, realizing his — and it’s almost always “his” — vision with little regard for the people whose lives are shaped by the buildings he creates. The notion of a “starchitect” is outdated, if it ever truly existed — a product of the media’s obsession with personality. But faculty see that students often arrive at Taubman with a certain trepidation about that reputation, and with a yearning to use what they will learn of design and construction not only to build their own careers but to right historic wrongs. For many, the Wallenberg Studio — the intense immersion into these topics and the knowledge gained while traveling together as a studio — becomes their seminal educational experience in exploring these topics.

Associate Professor Anca Trandafirescu has taught several iterations of the Wallenberg Studio that paid special attention to aspects of the American experience that architecture as a field has long overlooked. A recent class trip to Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, Monticello, revealed the keenness of her students’ concern for social justice: a tour guide, aware he was speaking to a group of architects, kept trying to draw the students’ attention to characteristics of the building. However, they wanted to talk about the people Jefferson had enslaved.

“My students are super sharp, and they were pressing him on the fact that you can’t take these two stories apart,” Trandafirescu says. “But I think that while the students are aware of the big issues that we all read about, they’re less aware of how to use their power — and that’s what I hope the studio imparts. When they start to practice, they will better be able to utilize their opportunity to influence who gets to have space and how they get to have it.”

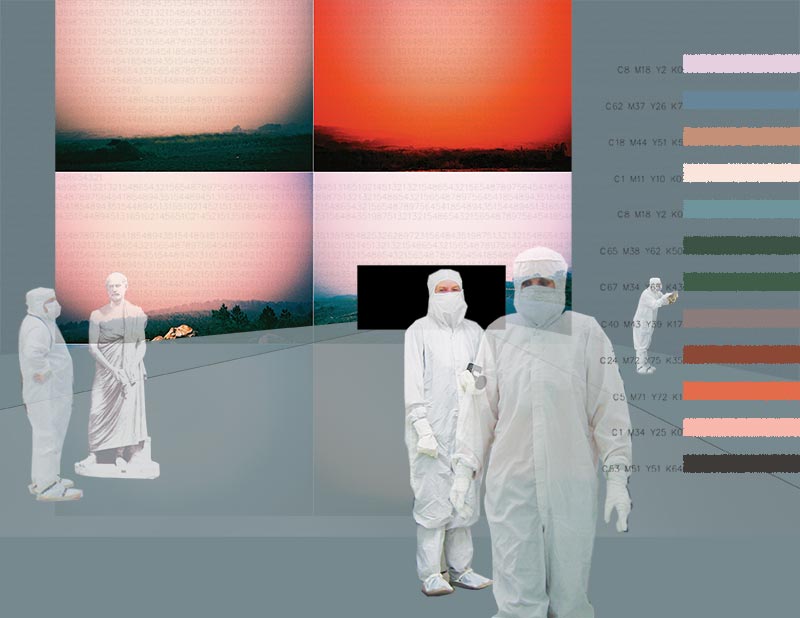

Wallenberg projects like Lindsey May’s are influenced by studios’ travel, such as experiences in the Arizona desert, Austin and New Orleans.

Architecture has always been political, notes Lindsey May, B.S. ’10, founder and principal of Studio Mayd, an award-winning practice in Washington, D.C. She received the Wallenberg Studio Prize in 2010 for her project “Variable Air Visitors Center,” a proposal for an infrastructure to support multiple extreme air environments for public visitation and research. In 2021, she received a League Prize from the Architectural League of New York for a portfolio that explored the under-celebrated residential work of small practices and the business realities faced by practices like hers. That ability to think about architecture as part of a bigger picture is something that her experience at Taubman College made clear.

“All my studios at Michigan reinforced that architecture has an impact on the context and people around it, but those ideas definitely came to a head during Wallenberg,” says May, who also is on the architecture faculty at the University of Maryland. “Architecture is the way that people across history have calcified their values — the things that we strongly believe turn into our material environment. And especially these days, I think there’s been a big realization and a reckoning around the good and the harm that architecture and design can do.”

The theme of the 2022 Wallenberg Studio is “Risk,” as chosen by Associate Professor Craig Wilkins, this year’s coordinator. In his own studio, he asked students, many of whom were preoccupied with climate change, to explore questions of action and inaction. He took his students to Galveston, Texas, in March to learn about coastline restoration. They also spent time in Austin volunteering with Community First! Village, which supports people coming out of chronic homelessness.

“Some of my students are talking about how Miami’s going to be underwater in about 10 years, so what happens to all those people down there?” he says. “A number of my students now are looking at the idea of immigration and borderless cities. When we think about risk, we usually think about risk to ourselves — we’re always calculating risk in a way that puts us at the center. I’m asking them to look through someone else’s eyes this semester, to think of other people as equal to you. If you do something, who’s at risk? Who’s at risk if you don’t do something?” Raoul Wallenberg could have left Budapest, Wilkins notes — it certainly would have been safer for him, personally. But he knew that failure to act would have been an even riskier proposition.

As Winter Term progressed, the eyes of the Taubman College community, and of people around the world, were drawn to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the biggest armed conflict in Europe since Raoul Wallenberg’s era. But to suggest that current events make Wallenberg or his namesake studio especially relevant today would be an error, asserts McLain Clutter, chair of the architecture program and an associate professor.

“The relevance is always there,” he says. “Of course, the present is sobering and upsetting. But in a way, it only brings to the surface elements of injustice that are less visible. The Wallenberg Studio is a culminating experience for students who have reached a level of maturity where they can think more critically about the social and political roles of architecture, and all the different ways that they can use their education as architects — this way of knowing the world — to impact society.”

— Amy Crawford