María Arquero de Alarcón is interested in bringing design and planning capacities to under-resourced communities that are typically overlooked by mainstream professional practice. Her voice becomes particularly animated when she describes the mutual learning that occurs from her collaborative projects with residents. She appreciates learning from residents of impoverished areas “their own imagination of what city they would like to see.” As an associate professor of architecture and urban and regional planning at Taubman College, Arquero de Alarcón works on producing design strategies that are sustainable, resilient, and culturally nuanced.

She acknowledges that collaborative design processes are “inherently messy and imperfect,” as they seek to advance different interests. But the approach has the advantage of harnessing the “boundless assets” from each collaborator. “It’s a very humbling experience to realize that you are learning from residents, activists, and community organizers as much as you contribute,” she says.

Arquero de Alarcon’s passion for this type of work comes from her own lived experience. In the early 1970s, when she was barely a year old, her family was among the first to move from Madrid to a freshly built subsidized housing unit on the outer fringes of Toledo, Spain, a mid-sized town. The community was part of a national plan to develop six satellite towns to move workers outside of Madrid. Ultimately, “the plan didn’t work well,” she says. The satellite towns failed to attract the anticipated industries and migrant workers. And the national government promoted other plans for regional development closer to Madrid that killed the satellite cities plan. “I remember going to demonstrations with my mom because we needed a school and a daycare center,” she says. Though the plan’s goal was to attract half a million residents, by the time she moved to Madrid for college years later, her district only reached 15,000. “And then, I discovered architecture could help me process my childhood experience and develop the skills to join citizen struggles for social transformation,” she says.

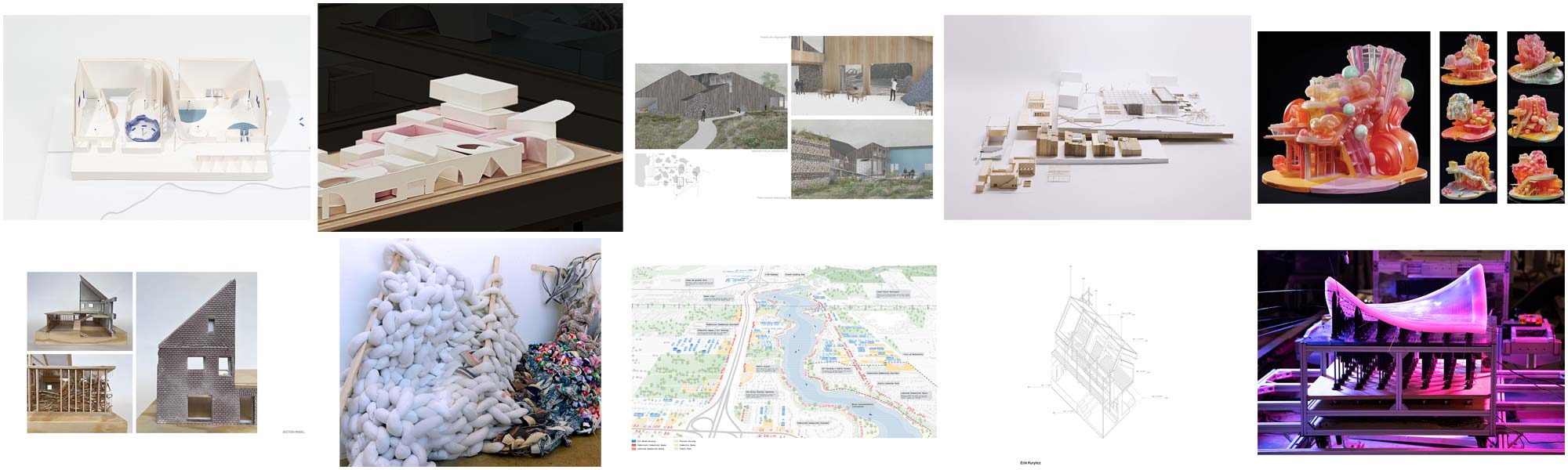

She joined Taubman College in 2009 and served as the Master of Urban Design degree director from 2015 until fall 2021. In 2010, she formed MAde Studio with her Taubman College colleague Jen Maigret. Their collaborative practice explores the agency of design in shifting the troubling environmental legacies in the Great Lakes region and Detroit more specifically.

In the early 2010s, the city underwent a multi-year planning process addressing decades of significant population loss. Detroit was trying to change its narrative, viewing vacancy not as a problem but as an opportunity for the development of a more sustainable city. One goal was to explore alternative uses for vacant land, bringing more nature into the city to lead to a better-quality environment “that will have a direct impact in the neighborhoods,” she says. One project, “Liquid Planning Detroit,” proposed green stormwater infrastructure to mitigate the impacts of the outdated combined sewer system. She explains that another, called “A Dozen Playgrounds,” “looked at the elementary schools’ courtyards as spaces of joy and neighborhood play.”

Her work in Detroit continues today. With Taubman College colleagues Martin Murray and Olaia Chivite, she investigates what has happened in different neighborhoods after years of financial austerity and dwindling municipal services. She also is part of U-M’s Detroit River Story Lab, a public-engaged scholarship and teaching initiative dedicated to leveraging the sociocultural, historical, and ecological centrality of the Detroit River in its adjacent communities. She explains that the Detroit River Story Lab invests in forms of storytelling that are inclusive, equitable, and complex. Working from the premise that the narrative infrastructure of regional communities is critical to sustaining social justice efforts, “the Lab builds on local partnerships to research, co-produce, and disseminate historically nuanced, contextually aware, and culturally rooted stories harnessing the symbolic power of the Detroit River in drawing out the lives and struggles of its adjacent communities,” she says.

Her work also has a global focus. Since 2016, she has been working with Ana Paula Pimentel Walker — an assistant professor of urban and regional planning at Taubman College — and a network of local collaborators and informal communities in the fast-growing southern periphery of São Paulo, one of the most environmentally diverse areas in the city. Residents in these communities are left with no other option to access adequate housing than occupy undeveloped land, she said. In the process, they are often criminalized for deforestation and water pollution and face eviction threats while enduring dire living conditions.

The goal of her participatory action research there is to “shift the narrative from illegality to permanence, empowerment and environmental stewardship,” she says. The project is supporting residents in their struggle to remain in place. These residents are “citizen architects and planners” who are “working tirelessly to secure shelter and resilient habitats,” she explains. She believes that the field of architecture “can play a decisive role building coalitions to bring about spatial justice” — the fair spatial distribution of social and cultural resources and the access to benefits they offer.

Arquero de Alarcón’s joint appointment with the architecture and planning faculty has fueled these research collaborations with colleagues, as well as students, across programs. “Taubman is a powerhouse for design experimentation and policy innovation and the support to faculty research enables student engagement,” she says. Even during COVID, her projects have continued. “That would not be possible in another institution without a public mission,” she says.

She marvels at the talent and drive of the students, who come from all over the world. The students “bring me joy because they are incredibly intelligent,” she says. “I learn a great deal from them.” She describes teaching as a source of inspiration and sees her role as “helping students build additional capacities and cultivate the imagination of what their future professional journeys can be.”

— Julie Halpert