The emerging field of urban technology may hold the key to solving some of the complex problems confronting today’s cities and residents, says Bryan Boyer, an assistant professor of practice in architecture at Taubman College.

“I think of urban technology as the use of technology, and specifically computation, to change how we see, shape, and inhabit the built environment,” he says. “The difficulty in defining urban technology is that almost everything in our world felt like new technology at some point to people who lived decades or centuries ago.”

For example, indoor plumbing, which is now taken for granted, felt quite novel in the 1840s when it was introduced in the U.S.

“The major transition we’re seeing now is that more things are becoming programmable,” Boyer says. “Plastic, metal, and concrete objects now have embedded software and are connected to the internet.” High-tech bridges with sensors, for example, can send signals to maintenance crews when repairs are needed.

The tools architects and engineers are using to shape the built environment are also becoming increasingly data intensive.

“As an architect, I was trained how to build a building,” Boyer says. “Now when we work on a project, we use many more sources of data, not just about environmental conditions but also about future occupants and space utilization. Increasingly, these applications, simulations, and data sources are informing decision making in the design process.”

The biggest transformation, according to Boyer, is how urban technology is changing the way people inhabit and utilize existing parts of the city, such as buildings and vehicles. The advent of ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft and online vacation rental marketplaces such as Airbnb and Vrbo demonstrate this phenomenon.

“There is more opportunity to gain greater efficiency and flexibility from existing assets,” Boyer says. “This creates an opening to think about how to do that in a way that’s meaningful to us as citizens and not just to business owners as capitalists.”

To date, much of the experimentation around rewiring cities has been driven by a small number of innovators, many of which are venture-backed startups with a narrow vision of success, Boyer adds.

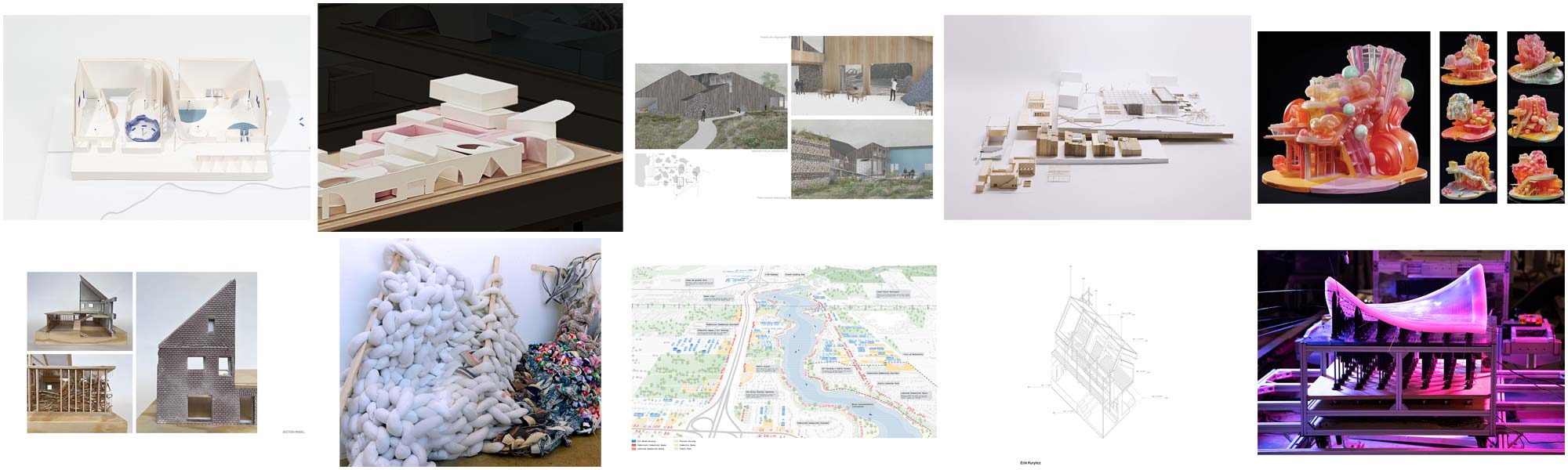

As the director of the new Bachelor of Science in Urban Technology program, which welcomes its inaugural cohort in January 2022, Boyer’s teaching focuses on how digital technology can coordinate the use of the city’s physical components and also explore ways to create a digital interface on top of those structural assets. Students will learn new skill sets such as coding and data science to ensure they are computer literate and understand how computation has changed commerce, society, and other aspects of urban living.

“There are many ways to effect change, and creating buildings is only one of them,” Boyer says. “The urban-tech students will be educated as strategic designers, but they will be working across different scales ― from designing the interfaces of digital services to thinking about the business model behind those services to considering policy changes that produce better outcomes.”

Ironically, Boyer never set out to be an urban-tech pioneer.

“I dropped out of college to create a tech company in the late 1990s and spent years working in technology,” he says. “Then I realized I wanted to shift my career and focus on architecture because I thought it might be a more direct way to have a positive impact on the people’s lives.”

Boyer went back to college to earn undergraduate and graduate degrees in architecture. After leaving graduate school in 2008, however, he concluded that architecture alone was not the answer.

“I realized that the practice of architecture can be like trying to push the world forward with a rope,” Boyer says. “The answers to meaningful questions — such as how to eliminate food deserts and ensure equal access to mobility ― aren’t necessarily best answered with a building or an urban plan. I became interested in what other forms of agency were available to someone with a design and technology background.”

In his quest, Boyer spent five years in Finland where he cofounded Helsinki Design Lab (HDL), a strategic design team within the Finnish Innovation Fund. From 2009 to 2013, HDL worked at a national level on carbon reduction, welfare services, education, and economic development.

“We gestated the idea of strategic design practice,” he says. “This is where a designer works across different mediums or scale in a way that is more highly engaged with policy, business, law, and economic leaders than with contractors and fabricators.”

As an example of this multidisciplinary team approach, HDL’s “Open Kitchen” project, a food entrepreneurship bootcamp, provided culinary training and bricks-and-mortar experience at local restaurants for street-food entrepreneurs. But the program also engaged government regulators, policymakers, and industry leaders in conversations about innovative economic development, eco-friendly food sourcing and waste handling, and intercultural connections that build stronger social capital.

In 2009, Boyer co-founded Dash Marshall, an architecture and strategic design studio based in Detroit and Brooklyn. Today he leads the studio’s “civic futures” urban innovation consultancy, which brings together multidisciplinary teams from design, technology, planning, and user research to collaborate on early-stage projects.

“We think about strategic design across the spectrum of physical, digital, and policy changes because they are all interconnected,” Boyer says.

Dash Marshall has done confidential project work for many leading corporations and nonprofit organizations. For Google, the firm created a workshop focused on the future of workspace and opportunities for community engagement. The Museum of Modern Art asked Dash Marshall to lead a workshop devoted to thinking about the future of philanthropy and innovative ways to strengthen relationships with donors.

Since joining Taubman College in 2019 as a visiting professor, Boyer, who is now on the faculty, has been excited about imparting his knowledge and experience to next-generation students, including those in the new urban technology degree program.

“I don’t expect that every student will go to work in urban technology after graduation,” Boyer says. “But they will carry a greater understanding of how cities work as complex systems and how basic technologies and computational mindsets work. They also will have abilities in design that will help them be great communicators and collaborators.”

―Claudia Capos