By Julie Halpert

Catie Newell didn’t become interested in architecture because she had a love for buildings. Instead, she was inspired by a long-held fascination with flying. “I had an interest in being up in the sky, and having different vantage points, and seeing different light and different landscapes,” says Newell, the director of the Master of Science in Digital and Material Technologies program and an associate professor of architecture.

She has incorporated that perspective in her current projects, which have received notoriety for the way she repurposes spaces through innovative material processes and use of light and darkness.

Associate Professor Catie Newell explores light and darkness in her practice and in the classroom

Newell has won numerous architectural prizes, including the 2011 Architectural League Prize for Young Architects and Designers. Dressed casually in steel-toed boots, jeans, and a long-sleeved shirt, her demeanor is down-to-earth and her voice brims with enthusiasm as she describes the work that has become the focal point of her life.

Her passion for flight led her to start out in aerospace engineering, but she quickly grew bored and craved an area of study that allowed her to create. After exploring a few other majors, she switched to architecture, which proved to be the perfect fit.

Her design work ranges from studying glass and materials to creatively repurposing spaces in urban, rural, and remote settings. “I have a tendency to make work that is very much embedded in the site that it’s located in,” Newell says. She explains that the singular thread in her designs is the “chase of the interesting reactions that happen with dark and light.”

In 2003, after completing graduate school, she began working for the architectural firm, office dA, where Nader Tehrani became her mentor and remains so to this day. But she ultimately grew weary of the 80-hour workweeks and became curious about what she could do if she were given the chance to create her own work. She applied for the Oberdick Fellowship in 2009 at the University of Michigan, which allowed her to both teach and receive funding for her own projects. She’s been at Taubman College ever since.

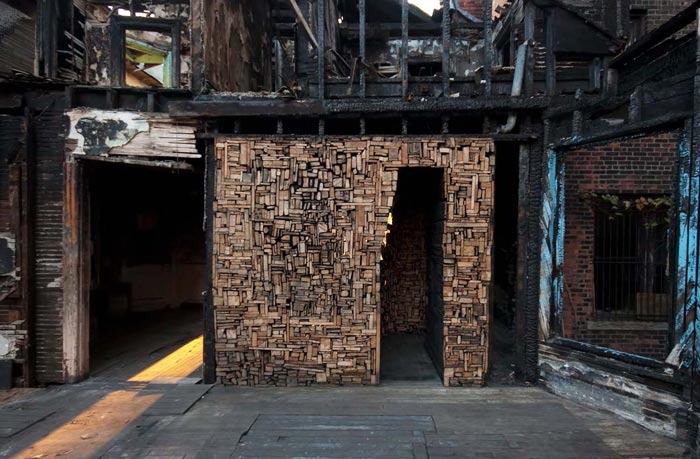

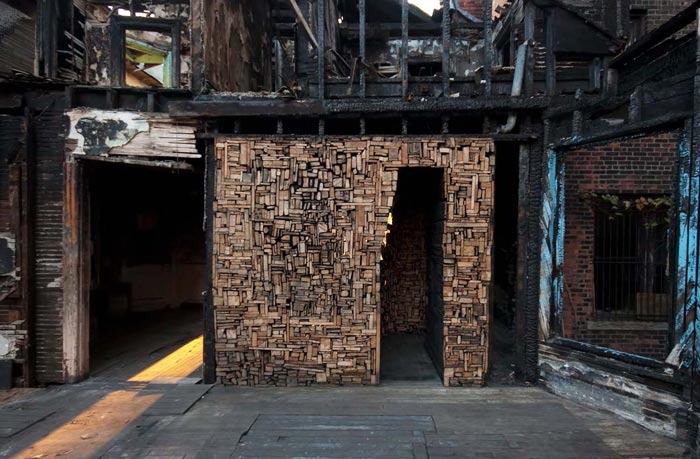

Many of Newell’s early creations have been immersed in sites that were difficult emotionally, like abandoned buildings in Detroit and a historic home that the city was trying to demolish in Flint. “I started to do projects where I could physically rework spaces that had been left alone and didn’t need to serve their original function,” she says. Ultimately, she grew concerned that her practice would be defined by working with these bleak sites. Eager for a break, she won the Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky Rome Prize to study at the American Academy in Rome in 2013. In a project called “Involving Darkness,” she studied how darkness and the night alter spaces.

In 2010, she launched her own architecture firm, Alibi Studio, in Detroit, the city where she lives. She’s currently renovating a building that will be her studio. “I’m trying to figure out how the work I’ve done before scales up to a building,” she says, adding that she is committed to staying true to her vision while dealing with such details as plumbing and building codes.

“Salvaged Landscape” in Detroit, Michigan.

The first full, building-size project for Alibi Studio is the reconfiguration of a barn in Hume, Michigan. It is part of an initiative by a group that commissioned Detroit-based designers and artists to transform 10 barns in that area. Newell saw the project as a prime opportunity to harness patterns of light and darkness. She cut a slice through the barn to let the sky come through yet ensured that slice was not just a simple cutout but a meaningful space. “When you walk through, it’s like the walls have actually been turned into the barn, and the barn face and sides and roof are all cut for that optical vantage point,” she says. “At night you can turn the lights on and it glows in the opposite direction, so there’s a day and a nighttime effect.”

The project, completed in September 2019, was all consuming. “I’m still recovering from it,” Newell says. Nearly every Friday, she would drive 2.5 hours to the site, then work the entire weekend. “I basically just disappeared for a couple of years. I was literally either in the classroom or at the barn.” Still, she welcomed the change in venue. “I’m an outdoorsy person and love the color of the sky and being outside, so it did have its treasures,” she says. “Sunrise and sunset last for so long, and my work has always been so interested in the shift to nighttime.”

Newell says her greatest sense of fulfillment comes from the surprise results as a project starts to reveal how it’s going to work with the light at the site. She recalls an exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of Art called “Overnight,” built in a studio in Detroit. It was installed on the ground level with floor to ceiling windows. There was no opportunity to test it in advance. One night, she asked the head museum security guard to turn off the exterior building lights. He agreed. “We all went outside and turned on my lights and turned off all the building lights, and it all just worked,” she says. “It was a very sweet moment where I felt like everyone who was around me got the project.”

Newell brings the concepts of her work at Alibi — where she’s focused on incorporating heart and intensity at a site while also challenging new ways of building with new fabrication technologies — into the classroom. In her teaching, she focuses on trying to figure out new ways of making that are paired with an increased use of technology, and she is particularly fascinated by how new tools allow materials to be deployed in a different way. She also appreciates the chance to take her students into real-world settings. Students in her advanced prototyping class and master’s studio recently headed to U-M’s Biological Station in northern Michigan, a place with almost no artificial light, to focus on wood and use it in ways that the discipline and industry have not yet envisioned.

(Above) “Secret Sky” in Hume, Michigan. (Below) “Overnight” at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

Some students experimented with mixing wood in clay to try and figure out a new water filtration system; others cut wood in an interesting way so it bends where it wouldn’t normally be expected to. “I roll up my sleeves with the students,” she says. She enjoys witnessing the different ways their approaches can bring new discoveries. “It’s very much like a working lab, where I learn from them.” Newell also says she is grateful for the opportunities that the University of Michigan provides for her own research and experimentation: “Michigan’s been very good that way. I don’t think I would be able to do the things that I do here anywhere else.”

Newell is particularly energized traveling to places with strange light effects — preferring those in cold places “because the higher latitude lines have greater shifts between day and night throughout the year.” In January 2019, she headed to Svalbard, Norway, the last inhabited town before the North Pole, for a conference on darkness. “I was finding my people,” she says with a smile. She has journeyed to Iceland numerous times, a place she describes as having “light and color that can be seen nowhere else.” She purchased a glass kiln there so she can continue her work while in that country, and she hopes to build a small cabin there, as well.

A self-described creative introvert, Newell often prefers solitary concentration undertaken in small spaces. She lives in a 900-square-foot loft that once was a photography studio. Her dream is to create several solitary research studios in unusual, unspoiled landscapes “that are dedicated to the location, true light, and pure night.”

In winter 2019, she co-taught a seminar with Sir David Adjaye — whom she met when they were traveling together as jurors for Seattle’s AIA Awards in 2014 — in which students were asked to create silence. Newell’s hope is that her creations, which she says are best experienced in solitude, offer a respite from the fast-paced world. “I think the world doesn’t get enough silence. I want the world to slow down in my work.”