Working with Associate Professor Sean Ahlquist puts students on the stage, in an exhibition, and on new career explorations.

By Eric Gallippo

FOR ALLISON BOOTH, M.ARCH ’20, working alongside Sean Ahlquist is about more than practicing cutting-edge design.

Although she’s drawn to the scale and novelty of his textiles- based work, it’s a specific audience Ahlquist has been designing for — children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — that made her want to get involved. ASD currently affects one in 59 children, causing challenges with social interaction, communication, and behavioral regulation. Booth’s older brother is autistic, and that led her to take Ahlquist’s seminar course in winter 2019.

“I like Sean’s direction and focus of research, and how the goal is to make something that benefits kids with autism and disabilities through architecture and new technology,” she says.

Allison Booth works the technology that makes “POND” come to life.

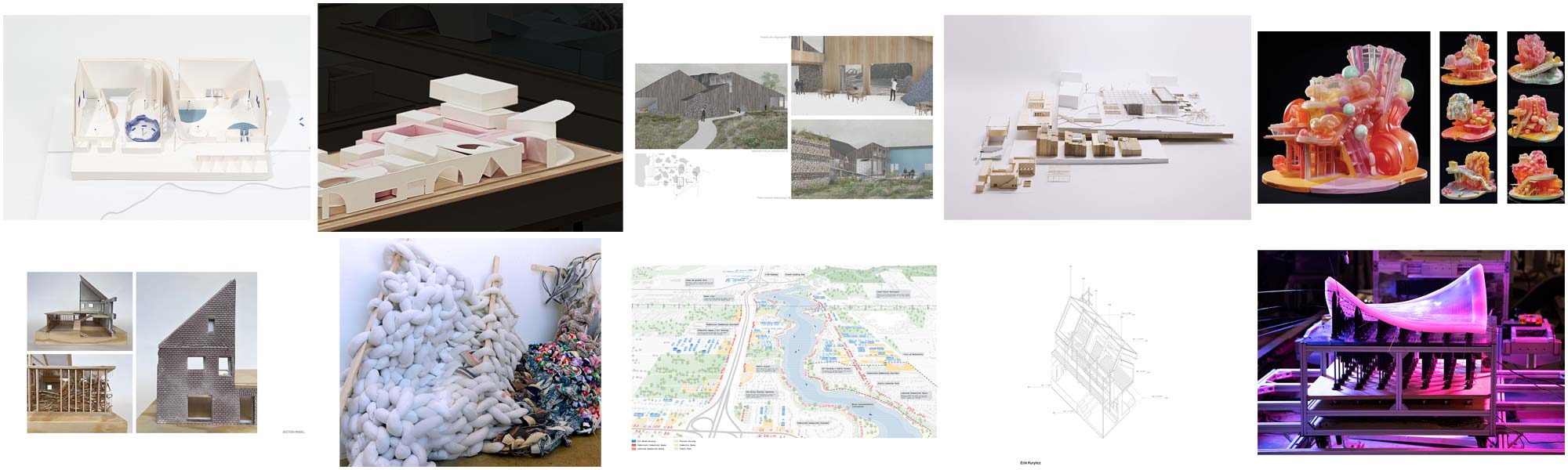

Ahlquist, associate professor of architecture, is a leader in exploring the architectural possibilities of knitted structures by using state-of-the-art, large-scale computer numerical control (CNC) knitting machines and homegrown modeling software. He and his team have developed applications ranging from educational environments to the automotive industry, including an ongoing partnership with General Motors.

The work is theoretical and groundbreaking, but also very personal. Ahlquist is the father of a 10-year-old girl who has autism and is nonverbal, common for up to 35 percent of those with ASD. For the last several years, he has been using his knits to build multisensory, tactile environments for children who — like his daughter — experience the world, and even communicate with it, through touch.

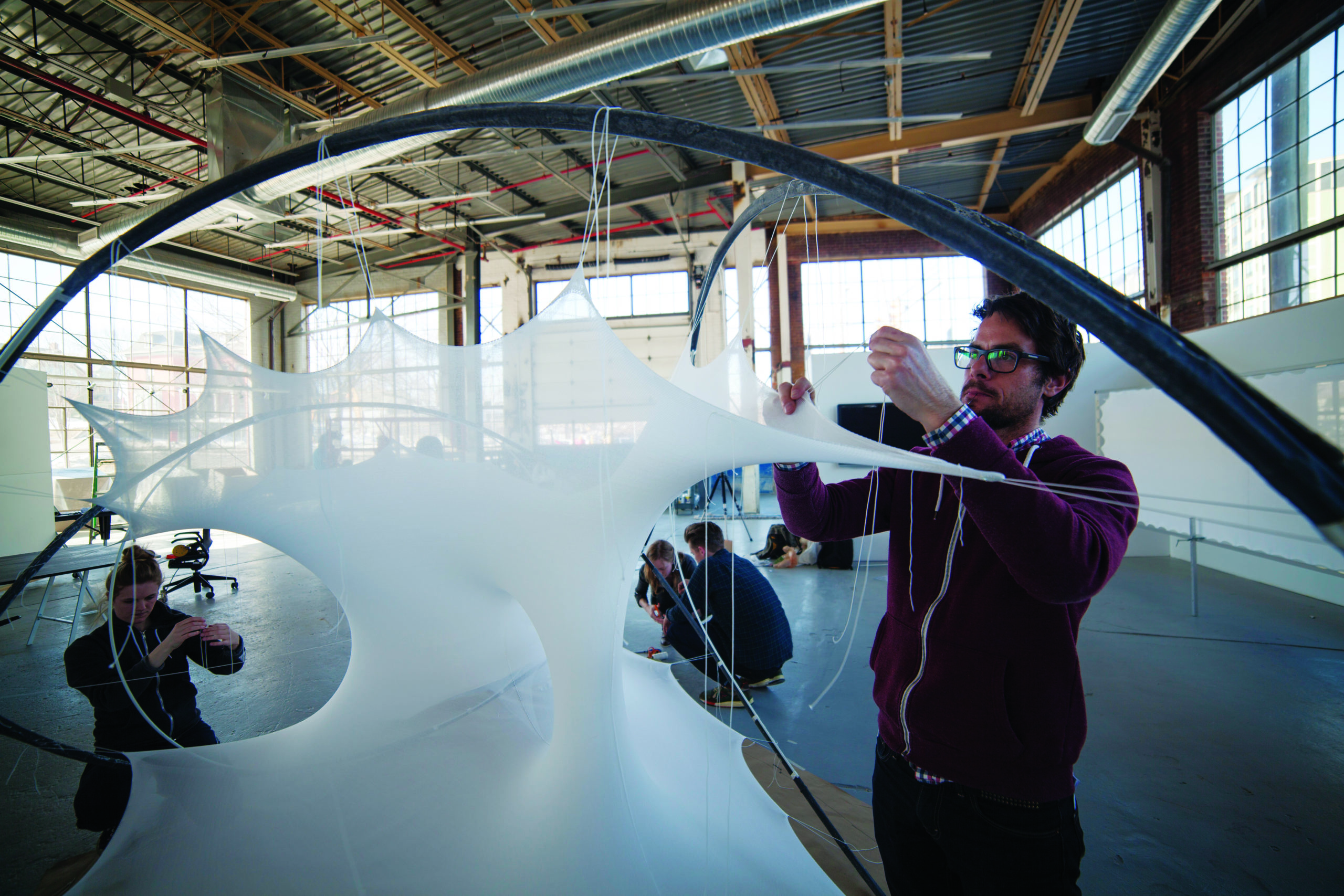

Made from stretchy fabrics that are modeled, programmed, and knitted in the digital fabrication lab (FABLab) at Taubman College and stretched across curved, fiberglass-rod frames, these playscapes often include multimedia projections that help draw children into the experience. The springy materials, which can include “smart” environmentally and structurally responsive fibers, are designed to be touch and pressure-sensitive and provide a rich and adaptable sensory experience.

Ara Ahlquist enjoys a test performance of “POND.”

And they make for some unique student projects. In June, Ahlquist and a team developed interactive set pieces for a multisensory theater workshop with collaborators from the Michigan State University Department of Theatre, aimed at engaging children with ASD. Booth was part of the team and helped design three textile environments and an array of visual projections in response to the scenes, songs, and characters in a play titled “POND.”

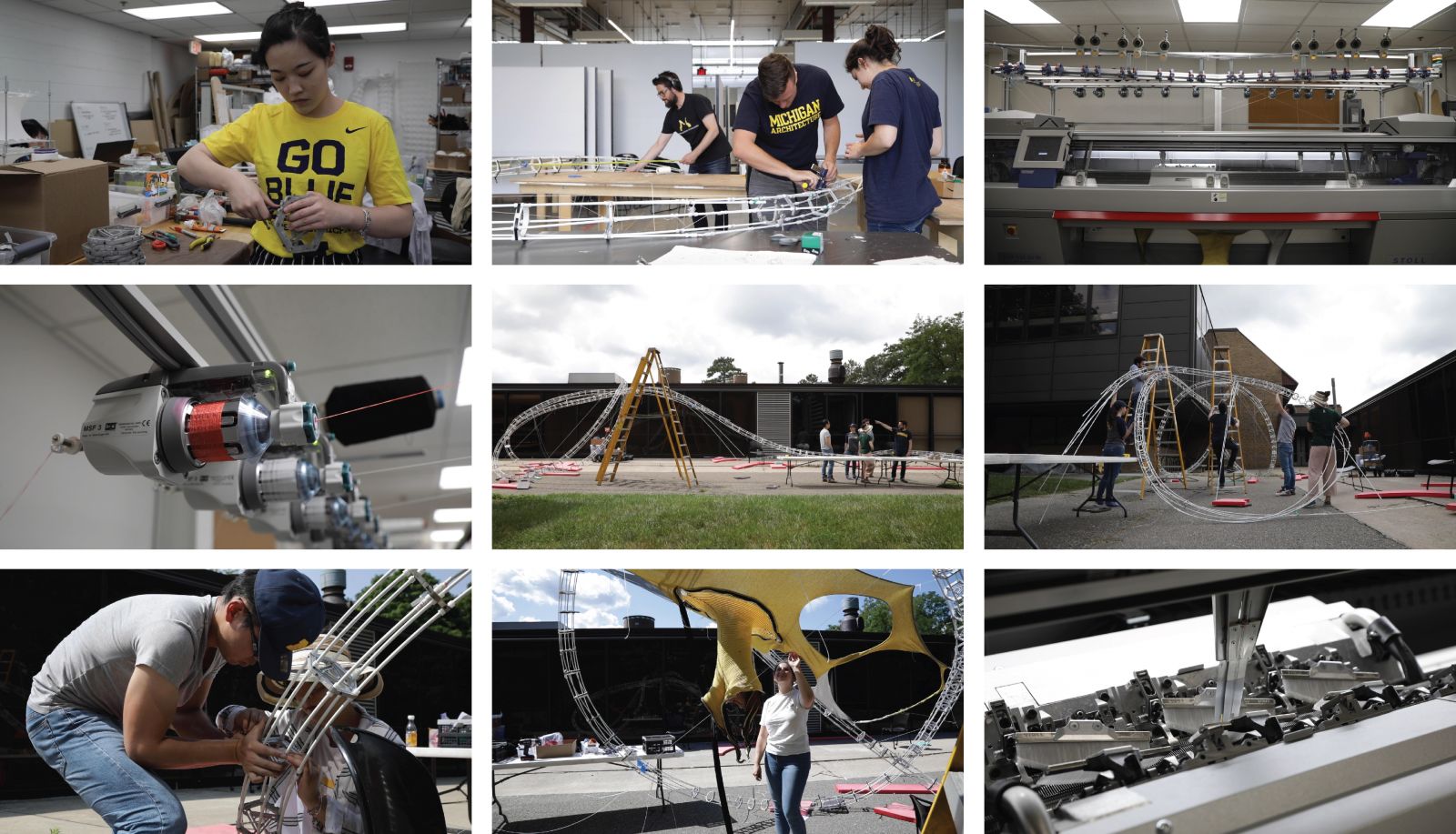

In August, Booth joined Ahlquist and four other Taubman College students to install his largest, most complex knitted architectural installation yet — for Exhibit Columbus in Columbus, Indiana. Standing 20 feet by 12 feet by 8 feet and scheduled for a three-month-long outdoor installation, the structure needed to support more weight and withstand the elements, as well as visitors’ interactions, while still providing a dynamic multisensory experience.

“The idea was to take the environments we’ve been designing for children with autism and look at them more as an environment for inclusive play in a public setting,” Ahlquist says.

The new demands called for new materials, knitting patterns, and framing structures. Ahlquist relied heavily on a team of students and former students now working as researchers to get it all done on deadline. “Each team member takes on very diverse roles,” Ahlquist says. “One might be more focused on specialized digital modeling, while another is focused on advanced methods of fabrication. It involves a steep learning curve for the students and coordination to pull everything together at the high level of precision that is required.”

Depending on their roles, team members operate sophisticated fabrication tools — including the knitting machine itself — plot intricate knit patterns, develop algorithms that translate 3D models to knitting programs and work with different fibers and yarn manufacturers to test and develop new materials.

“These different strands of research pull together to form a cohesive project that works, materially and offers opportunities as a therapeutic, inclusive environment,” Ahlquist says. “When multiple things are evolving, each student’s contribution becomes more critical because they’re having to think through how to design it, fabricate it, test it in and outside of the lab, and subsequently redesign it based on the information gathered.”

Prior to Exhibit Columbus in August, Ahlquist and students spent weeks assembling Playscape in Ann Arbor.

As part of her initial coursework, Booth helped explore the potential of knitting with more robust materials in preparation for Columbus. Three months later, she helped install the resulting structure. Through her previous experience with traditional architectural offices, Booth knows design can take years before anything is built. She enjoyed the smaller scale and turnaround time of working with textiles and now is learning to operate the CNC knitting machine to help expand Ahlquist’s research and possibly incorporate it into her thesis studio. “There’s so much freedom in this line of work and working with Sean,” she says. “He’s good at letting us have control over the design and explore our ideas.”

The collaborations often cross disciplines, too. For the Exhibit Columbus installation, Ahlquist collaborated with Maria Redoutey, a Ph.D. candidate in civil engineering, and her adviser, Assistant Professor Evgueni Filipov. After taking a class with Ahlquist in fall 2018, Redoutey saw parallels to Filipov’s work in the theoretical field of origami-inspired, foldable structures, and the teams have been exploring collaborative opportunities.

For Exhibit Columbus, Redoutey helped develop a bracketed rod system that could bear more weight than the previous single and bundled rod systems. Compared to her engineering background, where the focus is on planning, Redoutey says seeing her work become a reality was satisfying: “Working with Sean and his lab has been the most legitimate structural engineering experience that I’ve ever had. I’ve learned a lot in class, but being able to put it to use and see a physical structure come out of it has been really cool. And having the architecture brains in our group push the envelope and go for more novel ideas has been really fun.”

For this autism-related work, Ahlquist says students who connect to it on a personal level bring something unique to the project. “Even if they aren’t a perfect technical fit, it’s valuable to recognize that they can comprehend the larger vision of the research and have compassion for how challenging and extensive the pursuit of that goal can be. There’s often a more obvious commitment beyond the satisfaction of making,” he says. Last spring Ahlquist added his first team member with ASD: Martin Gregaro, a Master of Science in Information student who has Asperger’s syndrome, a high-functioning diagnosis of ASD. Gregaro learned about Ahlquist’s multisensory work for children after reading an article online and contacted him about summer work. He says Ahlquist got back with him the next day.

Gregaro was part of the Michigan State theater collaboration, then he oversaw the use of one of the playscape prototypes at the Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum for the month of August. He helped conduct preliminary research and form hypotheses on how children would engage with the different aspects of the structures. During workshops and other test runs with visiting children, Gregaro recorded data and helped evaluate what worked well and what didn’t.

“Growing up on the spectrum, I have a sense of the social issues these kids face,” Gregaro says. “Sean’s approach to creating sensory environments to help kids build better social and communication skills works really well.”

Gregaro previously planned a career as an archivist, preferably in a museum setting. He likes researching topics and presenting his findings. But now he’s thinking of changing that a little. He sees an opportunity to expand his work with Ahlquist into that space by creating interactive exhibits that are more inclusive for visitors with ASD.

Because much of the work is done with unknowns about how it will be received, Booth says seeing the payoff of children interacting with the structures is gratifying — such as watching kids who had never met before engage with one another at a theater workshop through the textiles, visuals, stories, and characters she had helped create.

“You work very hard making these unique knits and projections, and you’re not sure if it will trigger a positive response,” she says. “When you see it out in the world and the positive reactions, it’s really rewarding.”